Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art, London

15 April – 28 June 2015

by ANNA McNAY

Amedeo Modigliani (1884-1920) is perhaps best known for his paintings of nudes with elongated faces and figures, although some say he would have become a sculptor, but for continual ill health (he suffered from pleurisy, typhoid fever and tuberculosis as a child and died at 35 from tubercular meningitis, after falling into a life of drink and drugs in bohemian circles). This two-room exhibition at the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art focuses, however, on his works on paper, including 28 drawings in ink, crayon, pencil and watercolour. The majority are sourced from the collection of Paul Alexandre, Modigliani’s friend and first patron, and date from 1906-11, just after the artist arrived in Paris from his native Italy. During this time, he was constantly sketching, making as many as 100 drawings a day. Sadly, he destroyed many of these, deeming them inferior, or they got left behind when he – frequently – moved house.

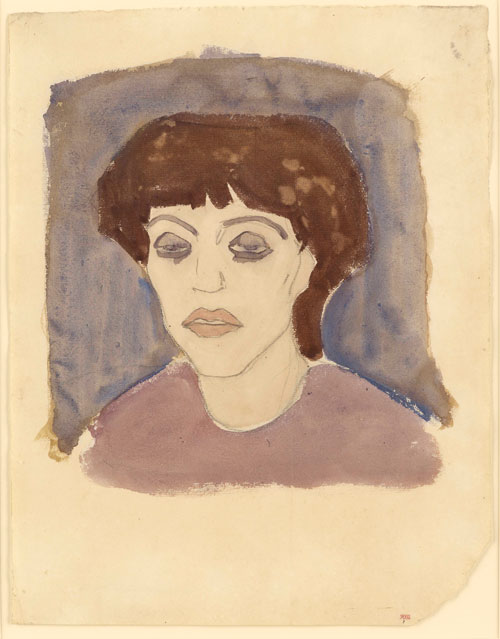

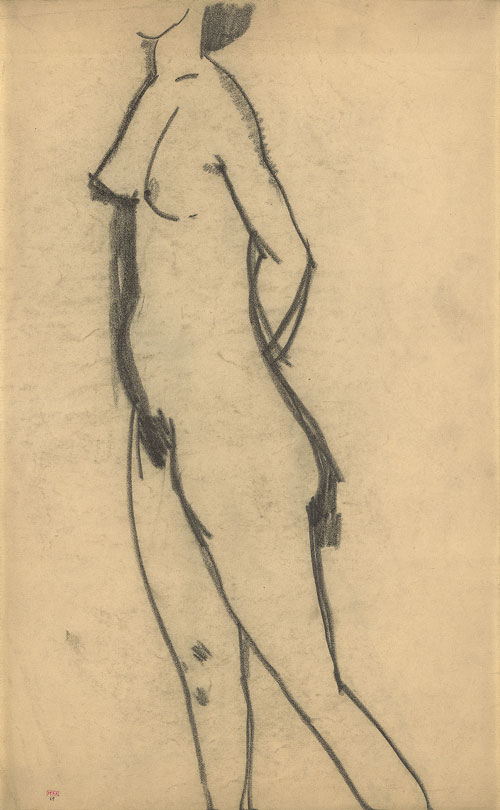

Engulfed by the Parisian avant-garde art scene, Modigliani began to develop his own unique and recognisable style. As well as being influenced by the likes of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) and the contemporary cubism, he also drew strongly on Cycladic, Etruscan, Egyptian, Greek, Roman, African, Asian, Buddhist and early Italian Renaissance art. Already his faces are seen to be attenuated and there is a simplicity to the figures, with their meagre outlines, a sparseness of markings, and yet a certainty to the lines, as if traced steadily from something underneath. There is a lack of shading and cross-hatching and no real attempt to bring about tone or shape to the curves of the figure, and yet somehow they are there and they emerge surreptitiously, like the trail of a silkworm or web of a spider, rising from the page. Modigliani’s gestures are free-flowing and graceful, and the works on display track the development of the artist as he studied the same model repeatedly, often making numerous drawings in quick succession.

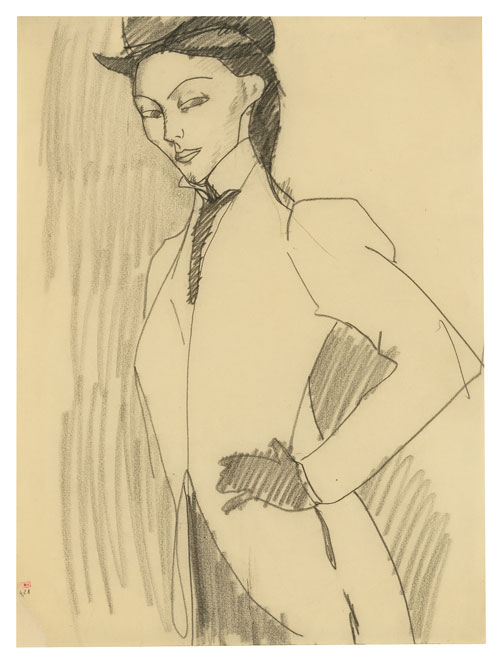

One work that particularly stands out in the first room is The Final Known Study for L’Amazone (1909), a black crayon sketch for Modigliani’s major early painting of the Baroness Marguerite de Hasse de Villers. The lines are crisp and sharp, the features exaggerated yet reduced, the finished piece clean and precise. As one of at least nine studies for this painting, the work is described as emblematic of Modigliani’s “obsessive search for the essential truth of character”.1

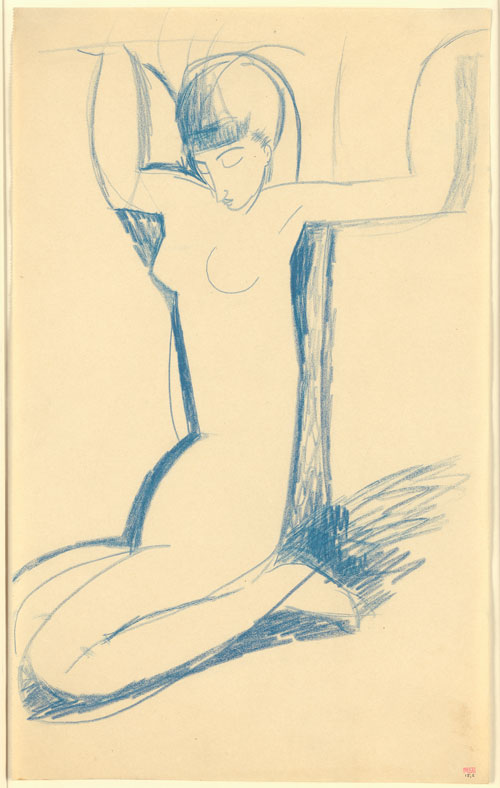

Another subject to which he was devoted was his early muse, the 6ft tall Russian poet Anna Akhmatova (1889-1966), whom he is known to have drawn at least 16 times. Three of these works are included in the show. One of them, in a gentle crayon, is Kneeling Blue Caryatid (c1911), which is distinct from the collection of caryatid works on display, being unambiguously female and having delicate, feminine features. Some of the other sketches, made during the period 1909-14, when Modigliani was focusing on his sculptural output, seem almost as if the artist took shapes from a box and put them together like a child making an image with fuzzy felt: almond-shaped eyes, a triangular nose, semi-circular ears.

In 1901, Modigliani had written to his artist friend Oscar Ghiglia: “… and as their inner meaning becomes clear to me, I shall seek to reveal and to rearrange their composition, I could almost say metaphysical architecture, in order to create out of it my truth of life, beauty and art.”2

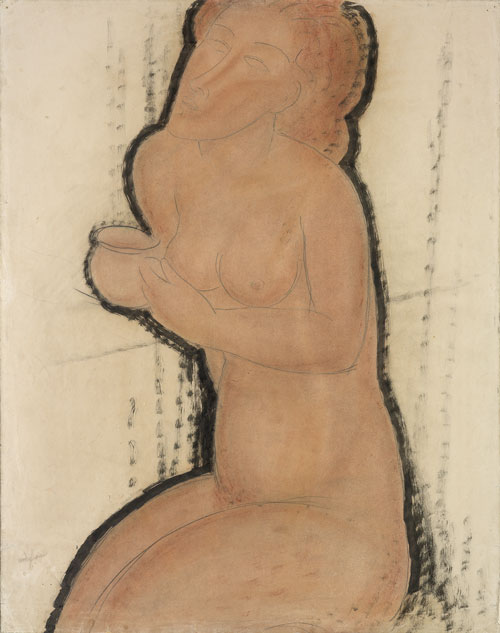

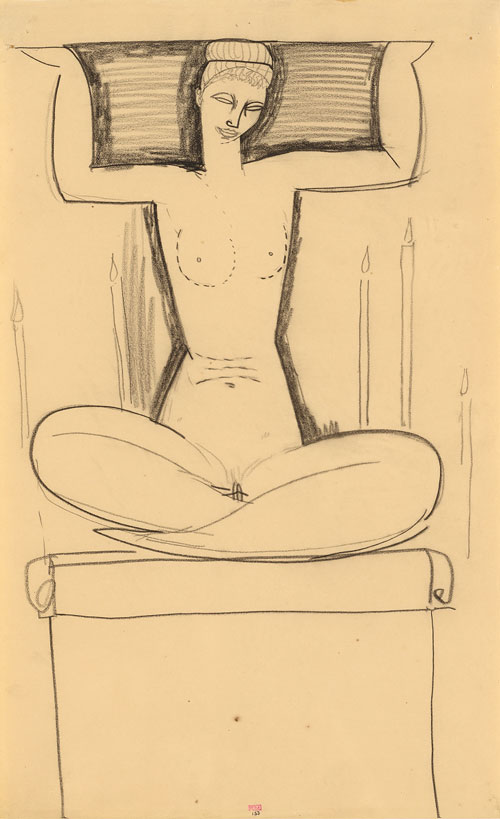

His drawings of caryatids recall their function only in pose, although, metaphorically, they might be seen to be supporting the burdens of life on their shoulders. In them, Modigliani has indeed taken from classical architecture, abstracting the elements of time and 3D space, rendering them into a new vision of beauty and timelessness, creating 2D templates, which might seemingly be rearranged with a subtle nudge. The serene, classical sketches, although drawn from life, emanate the coolness of marble sculptures rather than the warmth of flesh. Nude with Cup (c1916) might almost be mistaken for a photograph of an Egyptian terracotta figurine.

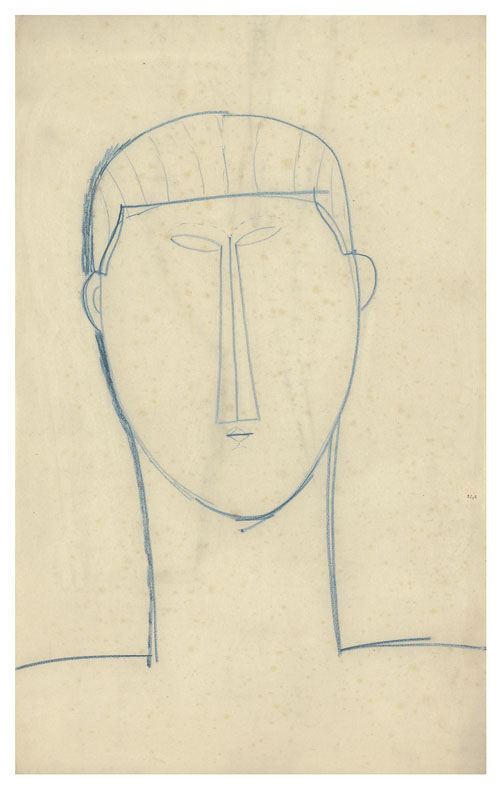

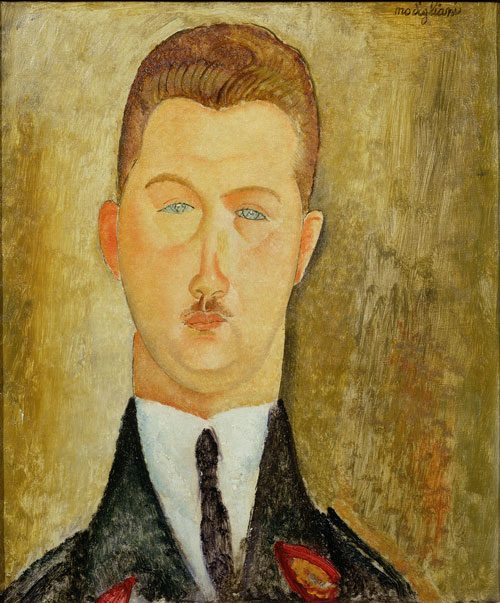

Modigliani’s sculptures and drawings fed into one another, as he developed his own language of reduction, linearity and abstraction. While simple and reduced to recognisable contours, his curves and elegantly flowing lines stand in contrast to the angular, geometric forms of the cubists. His symmetrical Head, Full Face (c1911) could, with its dashed outlines, be the design for a mask, while the oil painting Dr François Brabander (1918), with its cold and empty eyes, resembles more closely a death portrait.

As the artist put it: “What I am searching for is neither the real nor the unreal, but the subconscious, the mystery of what is instinctive in the human race.”3 Modigliani’s figures therefore blend the life model or muse with the sculpture, the present with the past, the 2D with the 3D, the marble with the flesh. Without much recourse to shading, it is Modigliani’s exploitation of negative space that gives both weight and volume to his bodies – and this is the negative space both without and within the figures. In Standing Nude in Profile with Lighted Candle (c1911), for example, the seemingly simple act of shadowing the outline, like a cut-out figure casting its shadow on the wall, defines the inner and the outer, without the need to make any further marks. Skilful and evocative, it is this rendering of space, this casting of shadows, even on a flat page, which, for me, makes Modigliani quintessentially a sculptor after all.

References

1. Modigliani: A Unique Artistic Voice. Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art, 2015. Exhibition Catalogue, page 30.

2. Ibid, page 9.

3. Ibid, page 9.