Lisson Gallery, London

22 May – 4 July 2015

by FRANCESCA WADE

The title of Shirazeh Houshiary’s eighth exhibition at the Lisson Gallery is as enigmatic as the works within it. The Smell of First Snow connotes purity, nature, beauty – but while snow is certainly visual and tactile, to be asked to imagine its smell is as unnerving as being forced to describe its colour. Wrong-footing her audience with unexpected sensory experiences, however, is the game in which Houshiary specialises. Born in Shiraz, Iran, in 1955, and moving to London in 1974, she first became known as a sculptor in the 1980s (her work was exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 1982, and she was nominated for the Turner Prize in 1994). She now works across media – painting, sculpture and sound installation – but in all its forms, her art has always striven to embody abstract concepts of spirituality and sensuality. The energy that imbues these pieces is infectious, and necessarily so: the viewer participates in the work by physically moving around the gallery: circling the glass sculptures to watch them sparkle from all angles; gazing up and peering down; approaching the paintings and inspecting them from sniffing distance, to reveal the secret symbols that construct their artful chaos.

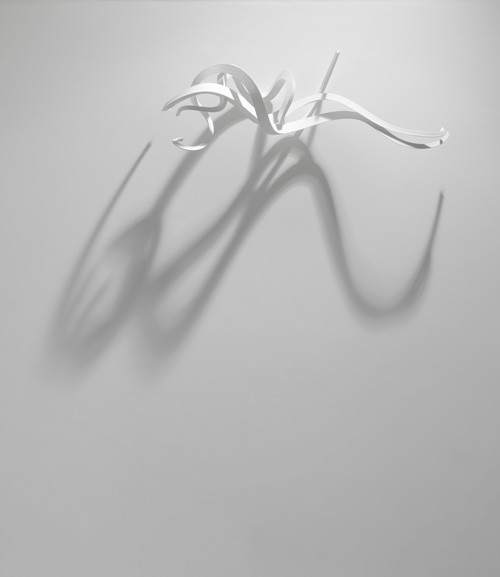

Across the gallery’s three rooms, two wall-based works, Allegory of Sight and Allegory of Sound, explicitly announce themselves as experiments in synaesthesia. These cast sculptures, of stainless steel and bronze, are coated respectively in black and white evanescent white paint, and snake across the wall like comets, or strings of DNA, or thin ribbons blown in the wind. Opposite Allegory of Sound stands Chord, a pedestal from which five similarly thin ribbons grow up like a tree. Evoking the five lines of a musical stave, the prongs interweave as they ascend. They are hardly discernible as individual threads until the top, where they peak in five erect crests. Without knowing the title, this wouldn’t be obvious, but when read as a visualisation of the way a complex piece of music shifts turbulently in key and tempo until resolving in perfect harmony, Chord reveals itself as another of Houshiary’s subtle, clever synaesthetic experiments.

The inquisitive viewer will observe that Chord is mounted on top of a thin mirror: if you lean in to peer down into the base, the whirling strands instantly duplicate. The walls, too, become Houshiary’s canvas: across them, diffusive shadows echo the three sculptures’ shapes, cast by carefully placed lights alongside the sun, which pours through the Lisson’s full-length windows (like crops, Houshiary’s work is seasonal). The effect is particularly intriguing with Allegory of Sight: the white sculpture’s grey shadow is more instantly visible than the physical piece itself, which blends into the wall behind it, extending its blankness into three-dimensional form. Nearby, the same light shines on Sylph, a pot-like sculpture made of translucent purple glass bricks, arranged in a twist. Like Chord, Sylph invites the viewer to come up close and gaze down inside it; from this perspective, the bricks form a dizzying staircase, pushing infinitely inward like a cyclone. The spiral brick sculpture is a form Houshiary has developed over her career, starting with 1994’s The Extended Shadow, which featured lead bricks covered in gold leaf. Now, she is more interested in light than luxury: as you circle the sculpture, the bricks shimmer in the sunlight, their reflection spilling out across the floor. By playing cunning games with light and perspective, Houshiary has found ways to make the most static form of sculpture come physically alive.

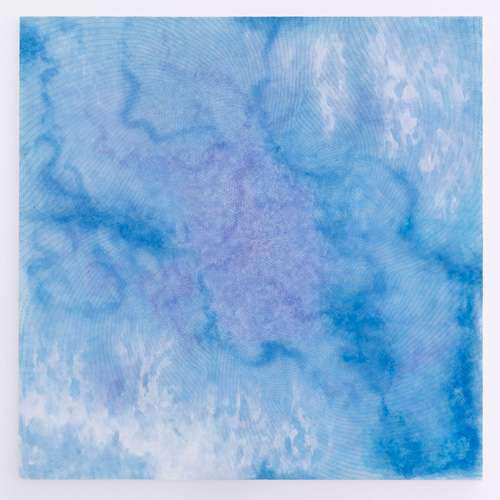

The paintings, however, carry the greatest intrigue of this potent show. Each canvas is saturated in deep hues, textured with blotches and splashes of colour (the mottled blues and purples of Zero, the deep reds of Rend, the black and blended indigo of Dying Light and Brink). Numinous and ethereal, they resemble immense and unknowable natural phenomena: oceans, sky, galaxies. They could be telescopic depictions of infinite space, or blown-up images of natural forms under a microscope – and, like both of these, their designs are apparently abstract and chaotic, but in fact are carefully constructed. To see this, again, one must approach: the paintings open up to reveal a myriad of tiny pencilled lines and symbols, which dance and swirl across the canvases in all directions, sometimes forming patterns, sometimes obliterated by a splash of vivid colour. From afar, the patterns seem continuous; up close, you see that they are diverted by seams and junctures, which cut off orderly rows of symbols, or distort them in a yawning ripple, mirroring the church window Houshiary designed in 2008 for St-Martin-in-the-Fields. The effect is mesmerising, and technically impressive: Reverie, for example, features a central motif arranged in an intricate circle, from which parallel lines fan out. Light blue pencil lines are highlighted by darker shading, which adds an almost imperceptible depth. There is a further layer, not discernible even by viewing close-up (the subtleties of Houshiary’s art do demand some prior knowledge): the symbols, which have webbed her canvases for the past 20 years, represent the Arabic words for “I am” and “I am not”. She invites and simultaneously denies her work to be read, embedding contradiction in every painting: the symbols are so small and overwritten by one another that their dichotomy is impossible even for Arabic-speakers to make out.

Many of the works are driven by a powerful centrifugal force: in Zero, the brilliant blues and cloudy whites explode at the centre into a whirlpool of purple. Seed, one of the most dynamic works, is striking for its stark blotches of vibrant turquoise on white clouds, dissected by rivulets of deep pink. The range of natural patterns the texture evokes is vast: the contour lines of a mountain range, the rings of an ancient tree, even the craquelure of old paintings or the whorls of smudged fingerprints, the unspoken presence of the artist. Two dark works, Brink and Dying Light, suggest the teeming eddies of a night sky. Each painting features two tiny, precise circles, one black and one white, which overlap, like an eclipse. The white circle seems to glow and radiate light outwards, and though minuscule on the vast canvas, immediately draws the eye: as a symbol of Earth’s simultaneous insignificance and significance, it beautifully encapsulates a central theme of Houshiary’s work.

In the artist’s last, sound-based exhibition at the Lisson, Breath (2013), the evocative chants of Buddhist, Christian, Jewish and Islamic prayers emanated from four screens, supported by images that portrayed the singers’ breath as it expanded and contracted. Like this exhibition, Breath’s driving sensory force was synaesthesia, but The Smell of First Snow sees Houshiary return to the forms that have become her signature: paintings and sculptures very similar to those which comprised her 2011 and 2012 Lisson shows. She has been making delicate patterns with Arabic words since the paper drawings Drawing around My Ghost (1992-3), while Self-Portraits (2000) inscribed calligraphy on to plain white canvases, creating texture using words. Her practice already pushes all sorts of boundaries, but this exhibition doesn’t represent an expansion of her own visual vocabulary. Nonetheless, her work is both aesthetically luscious and existentially probing: Houshiary deserves to be ranked among her sculptural contemporaries Anish Kapoor and Richard Deacon as a major modern artist at the peak of her career.