Nottingham Contemporary

4 February – 30 April 2017

by VERONICA SIMPSON

The timing of this show could hardly be better: an exploration of a period of great political unrest, characterised by widespread paranoia about immigration, stoked by politicians happy to appeal to people’s worst instincts in order to win votes, amid huge disaffection with the political establishment. Sounds familiar? Well, that was then, not now: The Place is Here examines Britain in the 1980s through the prism of a group of young black and Asian artists who were trying to penetrate the impermeable crust of western art world complacency, via painting, photography, installation, sculpture and video.

Featuring 100 works by more than 30 artists and collectives – including Eddie Chambers, Mona Hatoum, Lubaina Himid, Isaac Julien, Keith Piper, Ingrid Pollard, Donald Rodney, Veronica Ryan and Maud Sulter - its title, The Place is Here, is taken from We Will Be, a work by Himid, one of the leading figures to emerge from this scene. “We will be / Who we want / Where we want / With whom we want / In the way that we want / When we want / And the time is now / And the place is here.” These words are handwritten in vigorous capital letters on Himid’s cardboard cutout, which opens the second gallery: a defiant, life-sized woman, clothed in an angry patchwork of stickers and newspaper clippings of photographs of black civil rights leaders, topped with a glittering corset made of safety pins.

“We are claiming what is ours and making ourselves visible,” Himid wrote in the 80s. And many of the artists assembled here did indeed go on to make themselves visible, from 2017’s Artes Mundi prize winner, filmmaker John Akomfrah to Sonia Boyce, who was the first black British artist to have a solo show at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, in 1986. And Himid’s work over the past 30 years, as artist, curator, writer and teacher, is currently being celebrated in two connected but solo shows (at Modern Art Oxford and Bristol’s Spike Island, see below).

The Place is Here has been put together by Nottingham Contemporary director Sam Thorne together with Nick Aikens, curator at the Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, who first came up with the notion of examining this period in British art, resulting in the Van Abbemuseum’s 2016 show Thinking Back: A Montage of Black Art in Britain. He was inspired by the vividness – and relevance – of the work by this “group of artists and art students in the 80s, who were being presented with an art history which is entirely American, European and white … They are trying to find ways to negotiate their place in this history from which they are being excluded.”

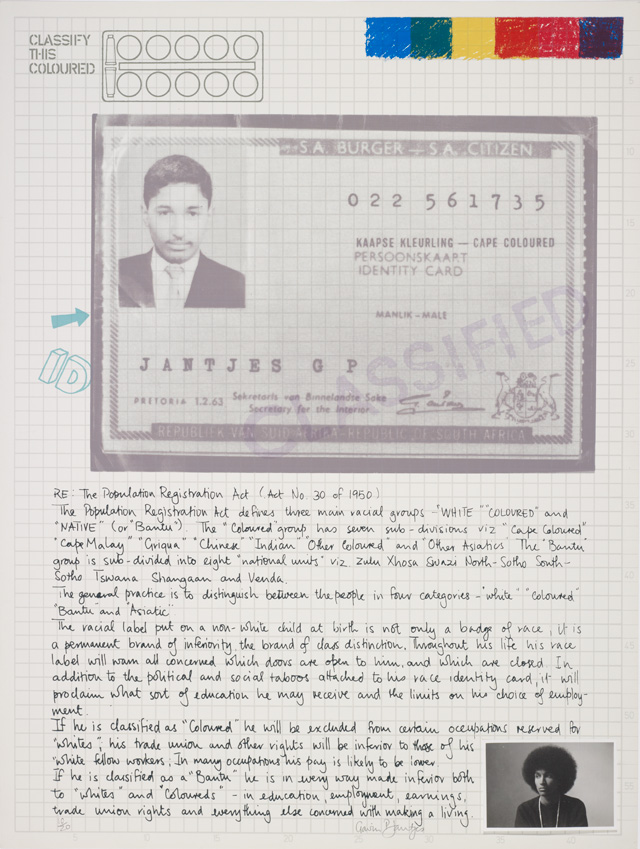

One of the most significant pieces in this “negotiation” is Gavin Jantjes’s A South African Colouring Book (1974-5). Here, Jantjes deploys the brown, gridded pages of a child’s colouring book to foreground his disturbing screenprinted collages, incorporating photographs, newsprint, drawings and printed, stencilled and handwritten text, through which he presents the grim realities of life as a “coloured” South African. Each page reveals a different aspect of this dehumanising experience, from the first page which offers a copy of Jantjes’s South African identity card, revealing his designation as “Coloured” (mixed race) – one of three race categories, White, Coloured or Native – which was further subdivided into seven subdivisions, under which Jantjes was termed “Cape Coloured”, a designation that carried with it a strict range of possible jobs, statuses and rights. “Classify this coloured” declares the instruction bar at the top. Another page juxtaposes a colouring picture of Hitler with a photo of South African president BJ Vorster, revealing in a strip of text Vorster’s former adherence to a pro-Nazi organisation called the Ossewabrandwag (Vorster was also responsible, while minister of justice, for Nelson Mandela’s life sentence). “Colour this whites only,” declares the instruction bar. Further on, Jantjes layers a newsprint report on gold bullion prices among other commodities on the global stock market over a news photo of black gold-mine workers – representing another kind of “commodity”; and, in a poignant subversion of Warhol, a photo of a black cleaning woman, down on her hands and knees, is multiplied many times over, accompanied by the instruction: “Colour this labour dirt cheap.”

This piece is one of the oldest here, created by Jantjes when he was living in Hamburg in the 1970s. It was shown at the ICA in 1976, an event that had a profound influence on many of the artists here, according to Thorne: “A lot of the artists in this show say that seeing this work was a formative moment. They say: ‘We realised we could talk about these things in mainstream galleries.’”

Where Jantjes’s work may now serve to remind us of how much has changed in South Africa, others are eerily current, such as Sutapa Biswas’s The Pied Piper of Hamlyn – Put your money where your mouth is (1987). Biswas’s allegorical work shows a corpulent, pink-faced businessman as the smiling rat-catcher, flipping a fat gold coin as he is pulled along in his rickshaw by an exhausted “coolie”, and trailed by a group of sombre south Asian children. Behind this Trump-esque figure, Biswas has collaged photocopies of pictures she took during her own travels in India, of grand temples at Ajanta and Orissa (now Odisha), apparently waiting to be looted and transported to Europe. Biswas has said that she wants people to respond to her work “on a visceral level”, as she creates “a context within which they are transported to a place somewhere within their own past and which visually and poetically unsettles perceptions of time and place”.

That eerie collision of past with present also permeates Boyce’s magnificent 1986 piece: Lay back, Keep Quiet and Think of What Made Britain so Great. It is a meditation on empire and identity, with Boyce’s own features staring out at us from the right-hand side of the frame, her face rendered both human and mask-like in solid paint, while the background across this and the other three panels whirls with decorative detail – a thicket of colourful, expertly sketched William Morris-esque black roses, prickly green leaves to the fore, interspersed with black-and-white crucifixes, caricatures of imperialist propaganda posters from India, Australia and South Africa that were commissioned to celebrate Queen Victoria’s 50th year on the throne.

Despite more than 30 years of the Commission for Racial Equality [established in 1976, it was superseded by the Equality and Human Rights Commission in 2007], and the western art establishment’s recent embracing of a more global, post-colonial viewpoint, the issues of who sets the cultural agenda (and how it is funded) are still fraught with inequalities.

As Aikens says: “These two contexts, the art historical … and the social historical, are very much in play at the moment. There is a political resonance with some of these artists but also within the art world, institutionally; how we’re looking at art, art history, our institutional remit, understanding the huge gaps, the huge leaps and jumps which need to be redressed, those two things again are absolutely at play.”

Where Gallery 1, Signs of Empire, deals with identity, and Gallery 2, We Will Be, considers power, Gallery 3, titled The People’s Account, examines the importance of whose histories are being recorded, and how.

Rasheed Araeen’s For Oluwale (1971-75) commemorates Nigerian migrant David Oluwale, who drowned in the River Aire in Leeds after a campaign of continual police harassment: the subsequent criminal investigation resulted in the first ever prosecution of British police in relation to the death of a black citizen. The face of Oluwale stares out from the frame in multiple faded printouts of newspaper reports, like a ghost, floating among the justifications and recriminations of the establishment.

If large works such as these pack an immediate punch, the smaller ones, such as Said Adrus’s Zeitgeist (1982-3), are no less powerful: a hazard-tape, yellow-tinted silkscreen print of police officers crouching behind riot protection, from another angle, Zeitgeist looks exactly like African warriors dancing behind their own battle shields.

Also in this gallery are two particularly powerful films, which present a much more nuanced, layered picture around incidents of violence between immigrant communities and the UK police. In Julien’s Territories (1984), he sets out with care and consideration (in contrast to the hysteria of the tabloid media’s very different version of events) to reveal how Notting Hill Carnival went from being a peaceful celebration of immigrant culture to a hotbed of crime and controversy (in part, thanks to ever-escalating police “interventions”).

Akomfrah’s Handsworth Songs (1986) is both a stirring exploration of the narratives around the 1985 riots in the Birmingham area of Handsworth and in London, as a result of brutal policing practices, and a poetic evocation of diaspora, memory and social evolution, created through his customary collage of sonic and visual newsreel footage and interviews, with photographs and archive material.

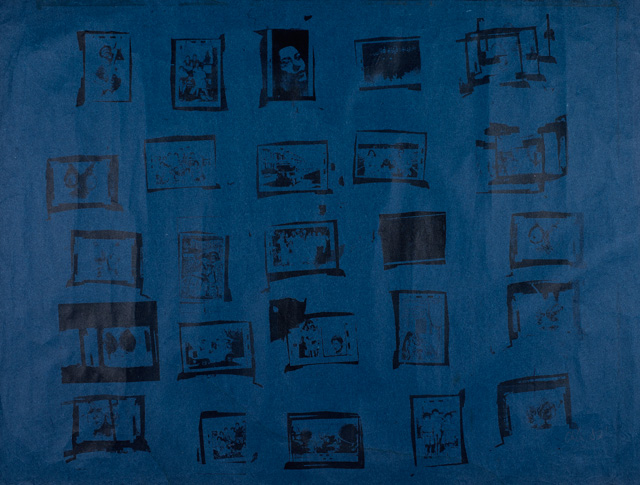

Both Julien and Akomfrah’s work emerged from a collective ethos, through the support of the Sankofa Film and Video Collective and the Black Audio Film Collective, respectively. And the importance of community and solidarity among these then underground artists and activists is highlighted by the presence of several archives – but for their existence, a lot of the show’s content, and certainly much of its contextual documentation, might never have survived. The Pan African Cinema Archive, a collection of films and related materials, compiled by June Givanni over 30 years, is present in posters, literature and imagery assembled in one section, as well as The African-Caribbean, Asian & African Art in Britain Archive (Chelsea College of Art), among others.

The ghost of Stuart Hall, a Jamaican-born cultural theorist, who died in 2014, looms over the show. A founder in 1960 of the New Left Review, Hall argued the case for including film within serious cultural discourse, and joined the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at Birmingham University in 1964. There, he played a crucial role in placing race and gender at the heart of its investigations. Akomfrah and Julien cite him as one of their heroes. And if there is a strong Midlands slant to the output in this show, it is probably largely thanks to him and his Birmingham alumni.

Thirty years on, there’s nothing shocking about the way in which these artists play with a whole variety of media and formats, mixing text with handwriting, poster-paints with photography, x-rays with sculpture, stream-of-consciousness filmic reveries with documentary interviews. But then this collaging, this deliberately jarring hybridity was something new, and uniquely appropriate to people whose identities and values were constantly challenged by the prevailing culture.

Why, I asked Aiken and Thorne, did many of these powerful voices, who clearly had an impact through the 1980s, not resurface until recently? Aiken attributes this partly to an assimilation of the black arts movement within the 1990s “culture of multiculturalism … this specificity somehow gets lost, depoliticised in a way”. But most western and European institutions’ preoccupation with the “narrow histories” of painting, sculpture and performance has played a major part. As he says, a show like this makes “you realise just how narrow those histories are”.

• Lubaina Himid currently has two solo shows, Invisible Strategies, at Modern Art Oxford until 30 April 2017, and Navigation Charts, at Spike Island, Bristol, until 26 March 2017.