Installation view, Jacqueline Poncelet: In the Making, Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (Mima), 2024. Photo: Jason Hynes.

Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (Mima)

1 February – 23 June 2024

by VERONICA SIMPSON

Jacqueline Poncelet (b1947, Liège, Belgium) refuses to be pigeonholed. It is one of the reasons that the artist, now in her late 70s with no sign of her material inventiveness or heightened chromatic intelligence waning, spurned offers of a full retrospective, or a monograph.

Well, she has signed up to both now, with the opening of a survey show of 50 years of making at the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (Mima). It is highly appropriate that this institute, founded in a gritty northern, post-industrial city, with collections of applied and contemporary art from the Cleveland Crafts Centre and the former Middlesbrough Art Gallery, should show Poncelet’s eclectic oeuvre. This restlessly questing artist has mastered many materials and techniques over her lifetime. And here they all are: there is clay in different forms and guises, from paper thin, luminous porcelain cups to thick ceramic tiles, their lustrous, glazed surfaces gouged into waves and rivulets the better to catch the light; there are assorted textiles including sumptuously colourful wool blankets and borderline-bonkers collages of carpet remnants. And there are glowing watercolours as well as stridently clashing patterns rendered in oil. There are expanses of wallpaper, densely gridded with Poncelet’s found images, their kaleidoscopic intensity refusing to be confined within the footprint of a mere wall (two of them have been plastered over the interiors of Mima’s two lifts). There is even the unusual combination of cast bronze and human hair.

Installation view, Jacqueline Poncelet: In the Making, Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (Mima), 2024. Photo: Jason Hynes.

How can such variety be shown coherently? That challenge fell to the curator and Mima’s artistic director, Elinor Morgan, who has chosen to show the work thematically rather than chronologically, arranging works by kinship in colour, texture and atmosphere. “This show reveals some of the threads that connect Poncelet’s many moments of reinvention without trying to fix their meanings in place,” says Morgan.

This is an exhibition powered by trust and time. Poncelet was given ample time, from winning the Freelands Award in 2021 – to celebrate and support a female artist who has “not yet received the recognition she deserves” – to the doors opening this month on her first full retrospective. Thanks to the generous £100,000 award, Poncelet was able to spend a good portion of the past two years visiting Middlesbrough, getting to know its robust history of making – from artisanal delights to heavy industry – and developing ideas with Morgan. As they discuss the show, Morgan tells Poncelet: “You’ve been resistant to being pinned down. But now you’ve had the confidence to lay something out. It’s what the prize allowed us to do together. And it’s been about trust and building that relationship so you can say what you want to say. One of the reasons you have not had more ‘success’ is probably the shape-shifting and resistance. But it’s what makes it so fresh and contemporary as a practice.”

Indeed. And thanks to the time spent in the city, so invested has Poncelet become that she has (hopefully) been commissioned to create a permanent public artwork within the soot-soaked footprint of the Victorian station (not officially confirmed at the opening, though, hopefully, it will be soon).

Leaf, 1995. Composite oil painting with fabric and photography, installation view, Jacqueline Poncelet: In the Making, Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (Mima), 2024. Photo: Jason Hynes.

And what a slow tour of the show, in all its diversity, reveals is Poncelet’s genius for manipulating the way the brain and eye work together – an almost mathematical understanding of how mixing domestic and architectural patterns and textures at various scales and hues can evoke a multitude of references and contexts. Or how you can, with a few brushstrokes, distil the vastness and timelessness of the landscapes she loves into a tiny booklet, almost vibrating with the atmospheres of the places and moments she is conjuring. Poncelet knows just how to make colours look utterly right – as in her watercolours, the harmonies and geometries of which positively zing – and also deliciously wrong, as in the crazy patchwork thing called Leaf (1995). It shoves bright and clashing wallpapers and textures together in a painted collage, which, according to Morgan, Poncelet configured and reconfigured endlessly until she found the most striking (and definitely not the most “tasteful”) arrangement.

Site specific wall works, installation view, Jacqueline Poncelet: In the Making, Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (Mima), 2024. Photo: Jason Hynes.

Poncelet is always in search of the poetic line between connection and disconnection. In an interview for Studio International in 2020, just before the opening of a show at the New Art Centre in Salisbury, Poncelot told me about the sense of displacement she felt as a child. Born to a Belgian father and English mother, she lived in Belgium until she was four but was then brought to live in England. Growing up in the Midlands in the 1950s and 60s, there were few foreign families. She was made to feel that difference: a memory that still stings - chatting at the opening of this show, she references the horror of having to wear socks to school that were different from everyone else’s: hers were hand-knitted by her grandmother, and they were patterned. She has long since realised that those differences – and the shifts in texture, scale and perspective she has noted and celebrated on her travels since – are now embedded in her artistic DNA.

The show at the New Art Centre brought together 35 years of making, from the mid-90s onwards. This one at Mima delves deeper into her back catalogue, and the ceramics she conjured in the first 15 years of professional life, and which, it seems, she turned her back on out of frustration, as the parochial 80s UK scene refused to accept clay as a true sculptural medium.

1970s porcelain work loaned by the V&A, installation view, Jacqueline Poncelet: In the Making, Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (Mima), 2024. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

It is wonderful to see the early ceramic works here. From the slip-cast porcelain works from the 70s (loaned by the V&A) in the first gallery – which Morgan’s eloquent essay in the forthcoming monograph informs us were arrived at through a complex process: “White clay cast from lathe-turned models, carved, indented, fired, then hand-polished with wet and dry sandpaper.” From their brittle delicacy, we move to the earthenware work from the late 70s through to the early 80s, including those inspired by her year in New York on a British Council Arts Fellowship. Poncelet loved the feral dynamism of peak Warhol-era New York, hanging out with Betty Woodman, enjoying the less siloed atmosphere of the US art scene, where pots could be exhibited alongside paintings without any fuss. She and her then husband, Richard Deacon, thrived.

An example of stoneware ceramics from the 1980s, installation view, Jacqueline Poncelet: In the Making, Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (Mima), 2024. Photo: Veronica Simpson.

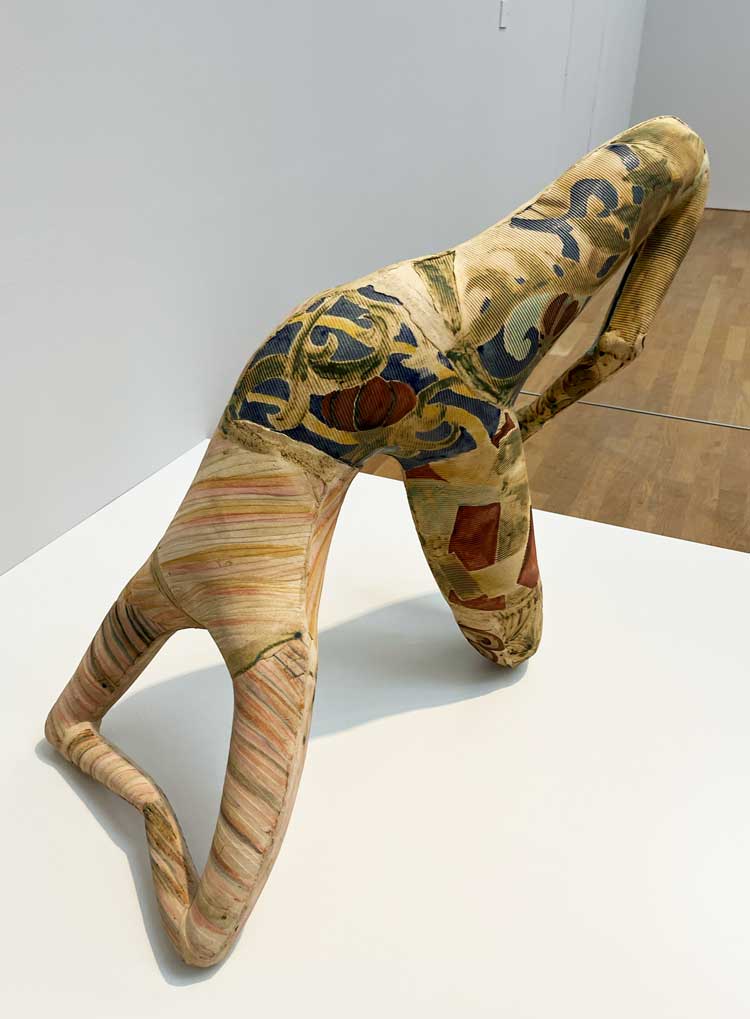

After she returned to the UK, her work moved away from playful geometries to a more fluid, zoomorphic, sculptural style. There are several of these works here – they make me think of mutant limbs deprived of identifying torsos, or torsos denied their mobilising limbs. Many of them have never been exhibited before, some loaned by Poncelet’s artist friends such as Alison Britton. These have been hand-built, sometimes using moulds and occasionally imprinted with patterns from wallpaper or cardboard. The decorations appear at times like tattoos, at others like veins or bruises, an impression compounded by the dark, reddish-purple palette. The anguish they emit is real, a result of her processing the sudden loss of her father, and the restrictions on her life and art imposed by parenthood combined with Deacon’s sudden elevation to the art firmament. Poncelet says: “I think it’s very interesting the way work gets muddled up with the emotions at the time, so when you meet it again, sometimes the emotions are there, sometimes they’ve gone away. When we came back from America, it was a very dark period. That work was made in the emotion of a difficult time. It was wonderful to see it and say: ‘Well, we survived it.’”

Tile from Danish residency, installation view, Jacqueline Poncelet: In the Making, Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (Mima), 2024. Photo: Jason Hynes.

If the 80s was a challenging time with definite peaks and troughs, one of the peaks was her frequent visits to the Danish ceramics manufacturer Bing & Grøndahl, from 1982 to 1986. Speaking at the launch of the Mima show, she says: “Scandinavian factories all had these artist studios – they were so enlightened. It was socialism in action, everyone ate in the same canteen. I went there and I started to play. I was never the kind of potter that makes their own glazes. I always thought of it as like choosing a paint colour. They had their own department of people making glazes. It was wonderful to have that facility - to say, ‘I’d really love a turquoise’, and there it is. So that’s why I’d play. I’d make the models at home, take them over and play.”

Installation view, Jacqueline Poncelet: In the Making, Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (Mima), 2024. Photo: Jason Hynes.

Another peak, you might think, was when Poncelet was invited to show some of her sculptural ceramics at the Venice Biennale in 1986 – her tangled clay limbs displayed on a white platform. Morgan says they were not well received at the time. Frustrated, Poncelet started to move away from clay, exhibiting a series of sculptures and paintings at Riverside Studios two years later. The 90s found her experimenting with found carpet pieces, which she collaged together in dynamic and unlikely combinations – the Tate bought one, but the art “cognoscenti” were consistently catty. She also played with print, photography and multicomponent paintings that hang together on the wall shouting contrasting conversations about domestic and architectural details (and we have these here, too, like the aforementioned Leaf). All of which seems highly in tune with today’s eclectic, multimedia, emotionally expressive times. At the time, while she waited for the contemporary art world to catch up with her, she found a fruitful outlet in large-scale public art commissions, working with Transport for London – on the wonderful Wrapper (2012) at Edgware Road, which first alerted Morgan to her work – and individual architects to find a way of expressing the emotion either within or around buildings through her often subtle, mischievous interventions.

Installation view, Jacqueline Poncelet: In the Making, Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (Mima), 2024. Photo: Jason Hynes.

In 2019, she was encouraged to delve into weaving by the Anni Albers retrospective at Tate Modern and went on to master the art during the ensuing Covid lockdowns. Some of the results are here and they are hypnotically beautiful in their palettes and their intuitive patterning. Poncelet has often said she is inspired by landscapes, urban or rural (she splits her time between Wales and Peckham, south London), interior as well as exterior. And in these latest textiles there is such a strong sense of her bringing the outside landscape into the gallery: luscious greens, blues, oranges, reds and yellows flicker and flirt across them: a Welsh summer garden in fabric form. These wool pieces, collectively termed Appearances Can Be Deceptive 2020-23, pay tribute to the woven textile traditions in Wales, and kente cloth from Ghana which, like hers, is woven in sections and then pieced together intuitively.

Wallpaper in the lift, installation view, Jacqueline Poncelet: In the Making, Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (Mima), 2024. Photo: Jason Hynes.

Works specifically created for the show include the aforementioned wallpapers, and a series of large vinyl stickers (Other Cosmologies, 2023) across the upper part of the first gallery. These have taken imagery from the four larger watercolours Poncelet has painted for the show, with sections magnified and then digitally printed. They are positioned in such a way as to draw our eyes to the architecture and light in the room.

Installation view, Jacqueline Poncelet: In the Making, Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (Mima), 2024. Photo: Jason Hynes.

While the textiles and recent watercolours live on in my imagination, one of the most magical discoveries were her Portable Paintings, watercolour books that she created while travelling alone in Seattle, in response to walks she made through urban and natural landscapes. Colours reflect shifts in seasons, light and tone, spilling, concertina-style out of their bindings like sunshine on a grim, wintry day.

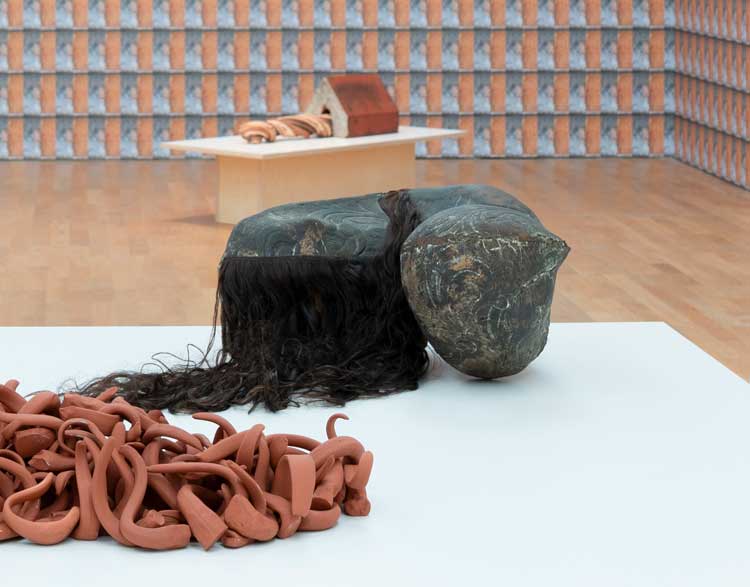

The aforementioned bronze and human hair, Bronze with Hair (1988), emerged from a fascination with “bog bodies”, the discovery of prehistoric people who have been found almost entirely intact - hair, clothes, skin - thousands of years after their death. One female bog body still had delicate plaits in her hair. This work responds to those tender, time-fossilised plaits, but it may also – on a deeper level – relate to an artist who felt her talents in clay were being buried under a thick sediment of misogyny and art-world elitism.

Bronze with Hair, 1988 (centre), installation view, Jacqueline Poncelet: In the Making, Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art (Mima), 2024. Photo: Jason Hynes.

Well, those layers have been lifted now. How does she feel about this show, after resisting it for so long? Poncelet says: “I have been slightly discombobulated by the experience. But it’s not going to change me.”

Morgan says: “For our visitors, it’s such a joy she has tried and tested so many materials. We are part of an art school [the School of Arts and Creative Industries, Teesside University], so it’s great for young students to see there are no restrictions as to what they can make. A lot of Jacqui’s work is very technical, but the materials are not that expensive.” Morgan is quietly satisfied that this show will reveal what an influence Poncelet has been “on a lot of people. In a quiet way, it pre-empts so many things you see that have happened in the last decades.”

• The Monograph will be printed in early May.